Previous tutorial, we took a look at the habitat of the test cases, so now it’s the time to closely meet with them. Here we will examine their genotype, phenotype and we will witness the genesis and death of them.

Genotype of a test case: Attributes

A typical test case would be made up of at least the following fields:

- ID: As we said, each case is unique, so that they are identified by a serial number. ID structure is specified when the templates are created, and it might look anything like: C01 (Case 1), S1_C1 (Scenario 1, Case 1), Login_1 (Login Scenario, Case 1), and anything up to creativity and the organization skills of the lead.

- Reproduction Steps: Each step is to achieve the condition of the case. It can start from launching the application and every action the user has to take (Launch the application > Click on the store tab > Click on an item > Click on the add to cart button) or can be more generic (Proceed to the item page > Clock on the add to cart button).

- Expected Result: What the user should be seeing or experiencing after executing the given steps. It is often a verbal explanation, but an optional visual can be added too.

- Result: It is made up of a list of several options. Common options for a result are pending (idle state of a case, waiting for execution), pass, fail, blocked (if the case cannot be executed for functional reasons), and N/A (if the case is not needed to be executed anymore).

- Comments: Any additional information the tester wants to give after the execution, like the explanation of a complicated result or the bug ID if a defect related is reported.

But there are generally more attributes included. Let’s take a look at some of them that you can adopt for your project’s needs (Or for fun? Making the testers work harder? Nihahaha?).

- Description: Short summary of what part of the functionality is to be verified

- Tester: If the tracker is assigned to multiple testers

- Date: Date of execution for the future reference

- Automated: Whether the test case is automated or not

- Bug ID: ID and a link to the defect report if the case is failed

- Pre-condition: Sometimes the steps to reproduce field can be separated to pre-condition. (Instead of specifying the steps to login the website in the reproduction steps, saying “Be logged in to the website” in the pre-condition).

Or things can get really ugly (not) for very specific kinds of testing some fields that are unique to only that type of testing might be used. For example, in localization testing the following ones are used:

- String ID: Unique identifier of a particular text to be tested.

- English Source: Reference for the translated text. If the translation does not correspond to the source, the case is failed.

Phenotype of a test case

Ever wonder what a test unit looks like (Not you dear, who is coming from the test plan tutorial)? Well, each case is unique and beautiful, so we have to embrace all of them with their differences. Nice, we are done with the SJW work, now we can get back to business.

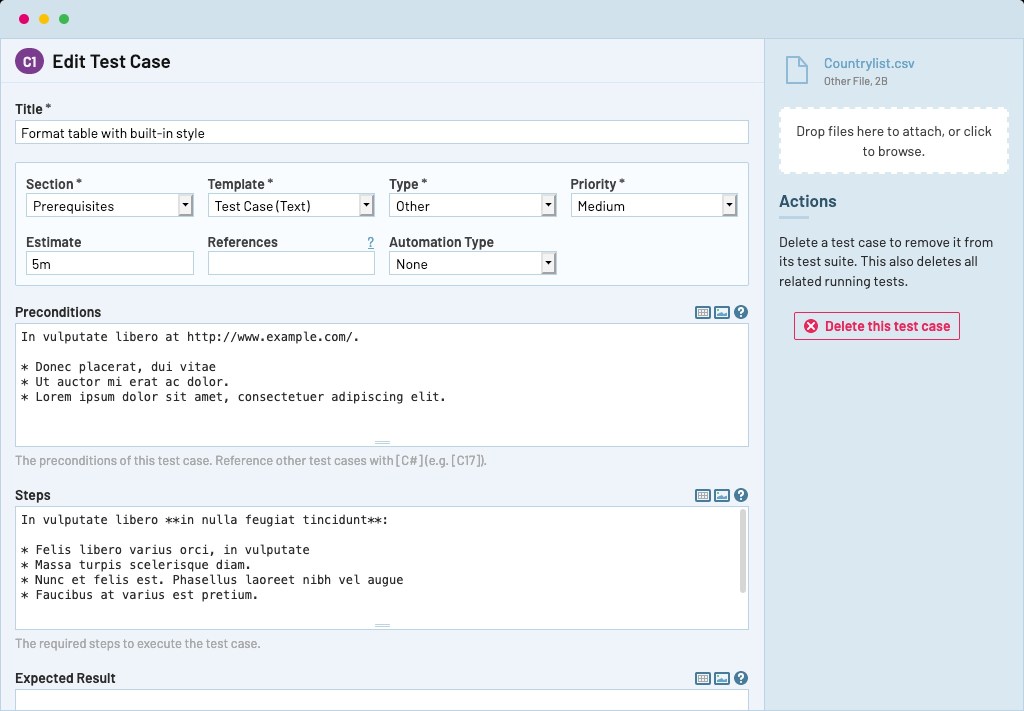

A test case is a record with the combination of the attributes we have discussed. It can be written in a test management tool, like TestRail, or might be a row in a spreadsheet.

There is no constraint on how a case should look, but as a rule of thumb, it should be easy to understand even for someone out of the team, it should include all the necessary fields and should be refined from irrelevant details. We will now, take a close look at how the units of a project can be structured in different ways. In this example, we are ought to test a login button’s functionality (I know, I know it’s a cliche example. But you know, simplex sigillum veri).

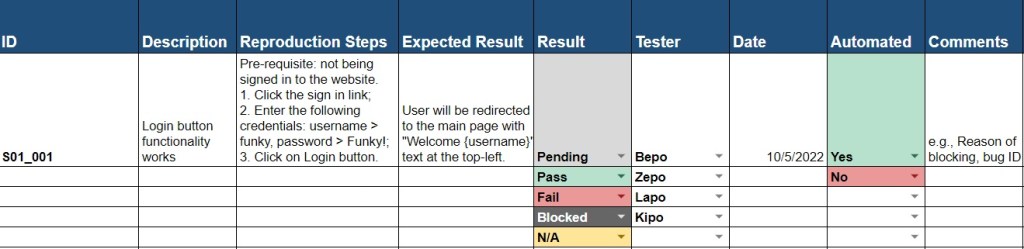

Case: Pacifist

- In this scenario, we want a little more documentation by adding a short description of what are we testing. Also, we will be receiving new builds constantly, so that we are keeping track of the date for future referencing purposes.

- Application is not complex with multiple states so that we are keeping the pre-condition in the same column with reproduction steps.

- Multiple testers can be assigned to the same tracker as there are a lot of test cases so we have a separate field for testers.

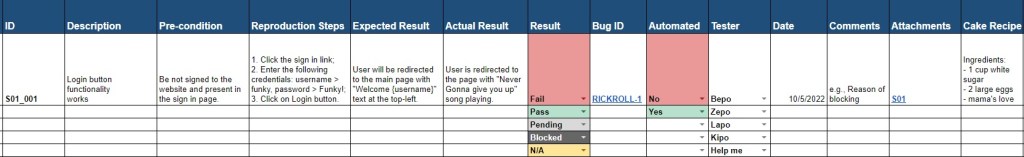

Case: Chaotic

- We omitted the execution date this time as the period of testing is short.

- Application is more complex, and a user can be in several different states so that we decided to separate the pre-condition from the steps to reproduce.

- Also, from the design documents, we predicted a huge number of defects that might occur, so that we also have the “actual result” and “bug ID” fields to give more explanation on the issue.

- Lastly, we are not marking the tester because each tracker is assigned to one tester.

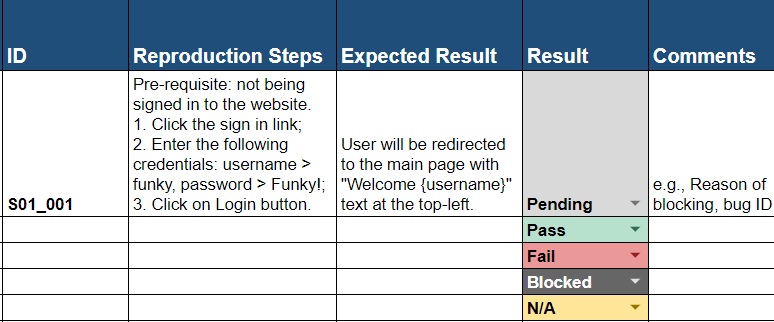

Case: Humblified

Case: ?!

Mind our author’s terrible sense of humor. We already sentenced him to rickroll for 10 hours straight.

Isn’t Test Case Writing Pain in the Gluteus?

A QA engineer quote says, “Why do we even bother preparing all those detailed units?”. (It actually goes more like “#$%@! this job”, but we interpreted it to be more readable for obvious reasons.)

Indeed, test execution without a detailed tracker can be possible for someone who has been in the project for a while or is already familiar with the type of application. But how about someone who is just trying to understand the project? The below list shows some of the reasons why not having well-developed test cases will actually cause an unpleasant sensory in the gluteus maximus in the big picture.

- With the test cases, we can cover more scenarios since if the testing is done randomly, we are truly leaving the fate of QA in the hands of the executor. No offense dear fellows, but it is a fact that testers can forget to cover or simply skip some cases for the sake of finishing early. When there are cases, we will eliminate to chance to mislead the client about the coverage.

- Test cases are used as documentation and reference point. If there is an issue in the live application, all the angry eyes will be turned to the testing team, but if we have the proof of the case related to the defect covered, we can smack the case on the table and take the blame out of the team. We may possibly make a scene by lighting up a ciggy and saying, “not guilty” and leaving the room. (Kids, do not try this at home)

- They guide people who need to grasp the application. It can be a new tester, a replacement for the lead, or a project manager. No matter who, when they read the trackers, they should be able to have an idea of the requirements and the design of the functionality.

- They make the process more structured, consistent, and detailed. For instance, a tester would not have to worry about testing the same scenario again, or not covering a case. Having a proper structure is also useful to provide meaningful stats to the client, or simply analyze them to make inferences.

See? We are not preparing them for fun (unless you are the victim of QA addiction, like us), and there are multiple reasons we need them.

Now, we know what kind of features a test case should include, what it might look like in different scenarios and why we write them. Let’s keep adding some author subjectivity by taking a peek at the best practices for test case writing (Funky QA approved ✔️).

Are my cases well-made?

Unfortunately, no. Unless you are following the approaches in the list below. Don’t worry, they don’t bite, just take a look at them.

- Pesticide Paradox: If the application is always tested with the same cases, it will get more immune to testing by the time as the defects in the tested areas are already tested.

To prevent falling into this paradox, remember to update them whenever there is a relevant change in the project, or a change in your understanding. They are not meant to be left alone after creation. - Pareto Principle: Defects are not evenly distributed throughout the application, and 80% of all the defects are found in 20% of the modules. It is also called “defect clustering”.

That means that small number of test cases can actually cover most of the application. Instead of trying to give the same focus to all the parts of the application, we should use most of our attention on testing the risky parts to minimize defect clustering. - Do not fall into the “Absence of Error Fallacy“. Testers might get tend to think that if nothing in the software breaks, it is good to go. False (In Dwight Schrute accent). An application can be bug-free but still be unusable if it does not follow the client’s requirements, so while creating the cases, always include the “positive” ones first. That means, first test the application according to the specifications, then write the “negative” cases, where we try to break the functionality.

- Exhaustive Testing: Trying every single possible situation for a scenario. For example, if an input field can take numbers ranging from 1-1000, testing each number till 1000 to validate the functionality.

This type of testing is extremely time and mentality (like duh) consuming and should be avoided almost always unless there is a very specific need for it. But Funky QA, how are we going to avoid it? Chill out grasshoppers, in the next chapter you will see 2 great methods to beat exhaustive testing.

- Keep the risk and priority in mind. While covering a scenario, we should not create the units randomly whatever comes to our mind. So, we should always keep the questions “Which piece of functionality is more important for the business?” and “What are the potential situations that might cause the defects?” in mind during the creation.

- Especially in Agile projects, do not try to perfection the cases. They don’t have to be perfect to be amazing. Seriously, there is no such thing as “tracker lock”, and they can be updated and refactored in the future depending on the situation.

- Don’t overcomplicate them. It is good to write detailed cases, but only detailed enough. There is no need to put irrelevant or repetitive information to a case. Keep them simple, because we will run them later, and we don’t want to spend more than 2 minutes on a case to execute.

- Group them in the relevant trackers. This may sound obvious, but it is a very common mistake to put a case into the wrong tracker or mapping to an incorrect scenario. If there are related trackers, we should double check the vague cases to place them in the correct modules.

Did you follow the best practices and perfectioned your test cases? YOU FAILED. We told to not to try to perfection them. Oh, you said figuratively. Cool then, we can finally execute the testing.

Execution. Under the guillotine, or on the rope?

We designed them, we created them… and now we will kill them! Time to execute the poor cases.

Actually, test execution can be the easiest part of testing (Well, on the other hand, it can be the most challenging part for game testing due to a lack of proper helper commands).

After all the trackers are created, and the build to test is verified for testing (by doing “Smoke Testing”. You’ll see, you’ll see.), each of the trackers are assigned to one or more testers for the execution. Testers manually run the cases by following the reproduction steps, and check whether what they experience (actual result) aligns with the description in the expected result column. According to the outcome, they can have the statuses below.

- Pending: The case is not executed yet and waiting for its fate.

- Pass: The actual result is same as the expected result.

- Fail: The actual result and the expected result is different.

- Blocked: Case cannot be executed due to a “blocker”. A blocker is a missing functionality that prevents us from completing the reproduction steps. To illustrate, we need to test the login button, but we cannot proceed to the login page.

- N/A: Test case is not available and there is no need to execute it anymore.

But we keep them alive as a hostage.For the reference, we don’t delete these cases but rather keep them in the tracker and mark as N/A. Unlike the blocked cases, the cases marked as N/A are registered to the coverage.

There are several important things to keep in mind while performing the testing. And they are really important, because we observed a lot of rookies (and even experienced) testers do these mistakes. Lucky that you will not be doing them.

- Let the client decide if the bugs will be fixed or not. We will repeat this point in the Bugs 101 tutorial as it is pretty vital. Peeps, we are not there to judge the customer or if their requirements are silly or not. If they gave us that requirement and if the application does not exactly match with the specification, we should fail the case and report that defect, no matter how minor it is.

In small teams where there are 1-2 people from each department, this behavior might be acceptable and even needed, but in most cases if you are eager on discussing the project’s needs, there is another job called “business analyst” that you might want to look into.

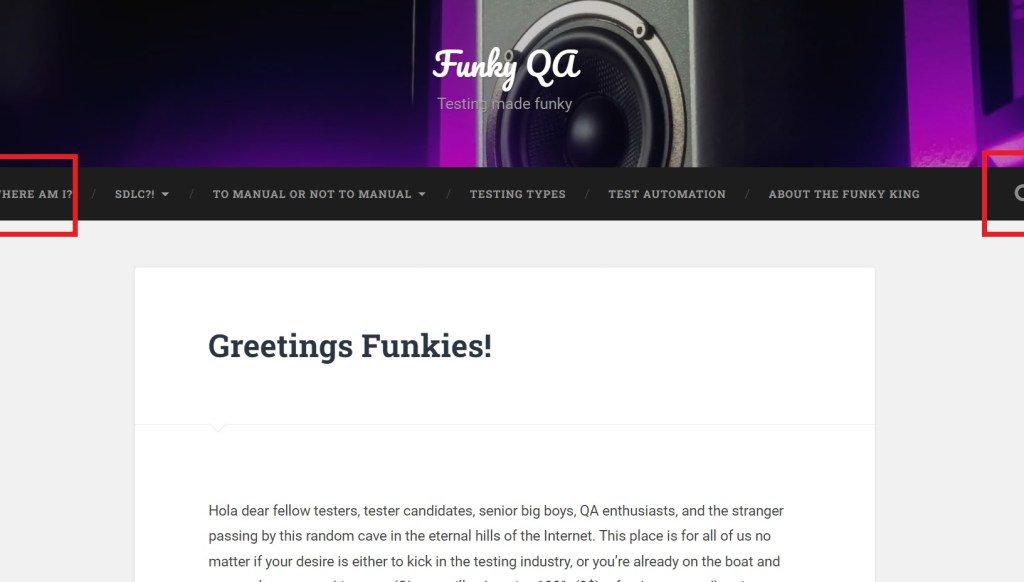

In the example at the left, there is a slight cutoff at the left and right side of the navigation bar on a specific device.

A bad tester will say: “Nobody will care about the cutoff; it can still be understood.”

A good tester will say: “I don’t care how small the cutoff is, requirements say that there should not be any error on the UI, so I will report this.” It is your choice to be a good or bad tester.

- Eliminate the assumptions. If we are even a little bit unclear about a requirement, we should immediately contact with the project manager or the client (Not with the developers. They are also retrieving the information from the PM and the client, so that they might make mistakes as well on the understanding).

- If the reproduction steps don’t specify the data to be used to execute the case. Try to think about the user’s point of view and avoid using dummy data (Unless doing a monkey testing. Test Types tutorial, honk honk).

- Last point is extremely important, everybody pay attention. Yo! I’m talking to you at the backseat (Always the backseat, right?). Don’t ever pass a test case without actually executing it.

Yeah, sure you won’t. It seems apparent before getting the hands in the dirt in the industry. But while doing the actual job there are days that you feel lazy (We’re humans, c’mon), and the cases look like they are going to pass, so you decide to just pass them without executing.

Or, more commonly the deadline is running up to you with the full speed and your lovely lead is pressuring you to just to finish the tracker. Believe us, not completing the task is always better than faking the work. Assuming you don’t have any moral code related to work, you can think about that more materialistic scenario where there is a defect in the live application and seems you already covered that defect with a pass. It will be a nightmare and it can even result in you losing your job.

TL;DR, kids, if you don’t want to be executed, execute the cases.

Now, you are the master of test cases! I mean almost. We still need to learn about some more technical ways to create the test cases. For the final scene, take a seat to watch and learn about the different design methodologies.

Trackers < Previous – Next > Black Box Design