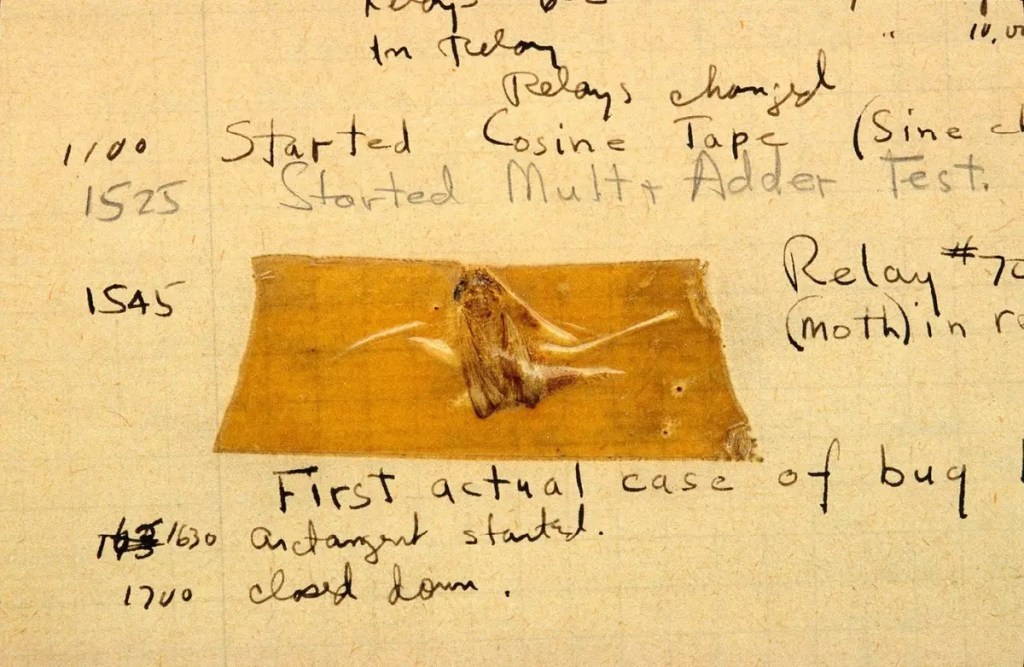

More than 60 years ago (If you’re reading this from the future that solidity is achieved, 100 years ago) when we were using gigantic computers, a computer nerd (Scientist, c’mon) at Harvard University found that one little work of nature that caused the glitch in their system.

His name, ironically, was Grace Hopper (Grasshopper, you get it?). Grasshopper then became the first ever tester in known history, and since then we as the cult of QA have been following in his footsteps to find and smash all the bugs to make the software world a peaceful place.

o7 to the General Grasshopper,

and also, mad respect for that brave bug that started the war against testers.

The digital evolution of the bugs

Of course, we don’t see physical bugs in our systems anymore; rather, we call the defects in the applications as bugs. Although it is a widely accepted term to identify the issues, it is actually more of a slang term for a “defect”. So, in our dump, we will interchangeably use defects and bugs.

If you are new to testing, in this and the following tutorial you will experience a great change in your perspective on software defects.

What actually is a defect/bug?

Everybody pays attention once again because understanding this simple definition is vital before we start getting deeper into the bug fauna.

A defect is any fault in the system that does not follow the business requirements and leads to an unwanted result.

People tend to think of bugs as application crashing or weird things happening, like the objects flying around as if they are in a Dali painting. In fact, even a simple typo can be considered a bug. We will discuss various types of bugs in another chapter. For now, to give an idea, we can group them into the 6 following categories with examples for each of them:

- Functional: A button is not clickable

- Performance: System crashes when 10 people using though it is intended for 100 people’s use

- Security: Users’ passwords are accidentally exposed (Holy moly)

- Compatibility: The software is intended to work on all browsers, but it does not work on Chrome (Chrome, really?)

- UX/UI: Elements on the screen are misaligned driving ODC peeps insane

- Localization: There are issues in the translations

Question. Are the software crashes during compilation (The process of turning the code into a working application) considered bugs as well? Well, not really. If there is a mistake in the code that prevents the program from actually starting working, we instead call them “compile-time errors”.

Programmers often deal with various kinds of errors that can actually lead to bugs in the working application. Errors have their own exotic ecosystem with such names as “null pointer exception (Programmer folks already started crying)”, “array index out of bound exception”, or “illegal argument exception”. The good news, these are not in our scope at all for the bugs tutorial, but we may have to deal with them as well in the future once we become bulked automation testers.

The last term we need to know to completely avoid the terminology confusion is “failure”. If the end-users face an issue in the deployed live product, we officially call it a failure. So, don’t ever think you are a failure because humans cannot be failures, but software can be.

Why there are bugs in my kitchen?

Counter-question: When was the last time you cleaned the kitchen?

Why there are bugs in my software?

Now, that one is a good question. We know that in the story of General Grasshopper there was a physical bug inside the computer. Now (I hope) there are no literal bugs in our applications, but why do we encounter with defects every once in a while? (For the users. Testers see a million of them every day. See, The Art of Exaggeration by Funky QA)

Bugs may occur due to a wide variety of reasons and are very specific to the project. Assessing the reason for the issue is the crucial part for the bugs to be slayed and fixed. Let’s take a look at 6 of the common causes.

- Database/Backend

Especially in bigger projects, variables are not hardcoded into the program and are stored in the database to be used in the application. Missing records and connection issues may cause the values not to be displayed or used in the software. - Platform

Different devices or browsers have different specifications that would result in compatibility issues. Such as, a specific modern tool that is used (such as the grid layout, CSS fellas 😉) to implement the design may not be supported by older browsers and cause a UI issue. - Unexpected user behavior

We cannot expect the users to use the software according to the requirements. By using error guessing and ad-hoc testing techniques, we can catch these bugs, such as using non-numeric characters in an input field causing the program to crash. - Unclear requirement

For this one, we should’ve had to blame either the developers by saying “developers’ misunderstanding” or blame the business analyst for giving the developers unclear specifications. - Implementation

And here we can finally blame the developers for making mistakes in the code or implementing incorrect variables in the UI. But seriously, don’t ever blame the developers. We will point this out several times in this tutorial.

Why do we write bugs?

First of all, bug reports and bugs are also used interchangeably, so if you hear the term “bug writing”, we actually refer to defect raising. Alright, so here we go, why do bug reports exist?

- To have a structured approach

The primary purpose of logging defects is obviously for them to be fixed. In this sense, reports are the communication medium between us and the developers. If we merely message the developers to fix the bugs, it would be nearly impossible to keep track of the bug lifecycle. - They are used as a reference

For the team members, if there is a similar bug occurs in the future, we can refer back to the previously written similar bugs to have an idea about what is going on and it helps us to report the new bugs more easily.

From the client’s perspective, if there is a failure in the live application, they can investigate on whom to blame and yell at by searching to see whether there was a defect report entered for the issue, and if entered, what has happened during the lifecycle. - We can use them for statistical analysis purposes

Similar to one of the reasons for creating test cases, bug reports can also be used to find out the most problematic areas in the system. They even have an advantage over the test cases as they can be made more detailed analyses as we include a lot of different attributes in the reports, such as the severity. Thus, in this example, by looking at the trackers we can see what areas are more affected, but since we have the information about the severity, we can see what areas tend to be affected more severely.

A Bug’s Life(cycle)

Remember the “Environment Setup” step of the STLC? Good! But we don’t have anything to do with that right now, but we will learn about a different one, the “Bug Tracking” phase.

Pop-quiz

Our newbie tester Kipo has been assigned to the tracker reviewing the UI of the newly added articles and has encountered a typoe in the Bugs 101 page. Having known that the client, Funky King, is very strict about not having syntax mistakes in the posts, what should Kipo do now?

🙈-) I don’t know what type you are talking about. Nobody would care anyway, right?

🤡-) OK, I saw the typo, but why should I bother reporting and tracking it as a bug? I will just direct message the UX writers or the project manager for them to immediately fix it. Me smart.

🏆-) I should be following the guidelines, so will raise the bug through the standard way.

😱-) Why are the answers written in the first person singular? Am I Kipo?! Let me out of here!!

(While the author is still dealing with the angry clowns and monkeys, you can proceed to the next part where we learn about the reasons for writing bugs)

As long as we are 100% sure without an excuse that a discrepancy with the customer expectations is not a feature, we should report that fault as a bug. We will get into the details of how to write a bug report in the following chapter, and for now, we will take a look at a bug’s life from its birth to death.

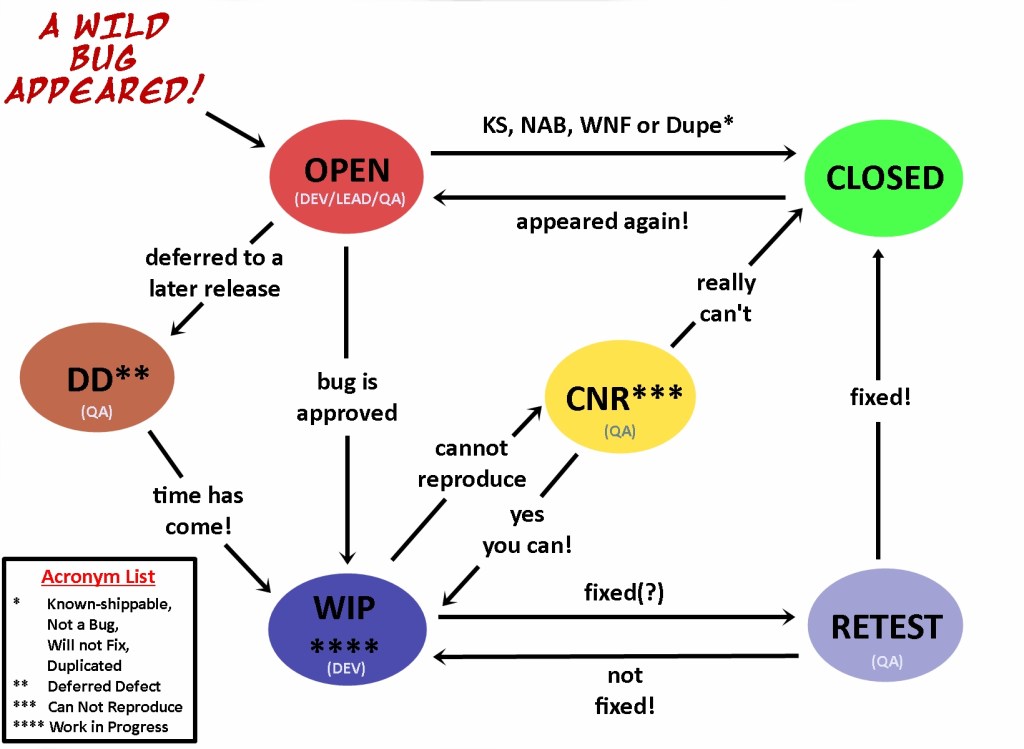

Though sometimes there might be more stages included in the lifecycle, the following steps will apply to most of the projects, and once you grasp the general idea, it will be easy to learn the project-specific phases of bug tracking.

Status: State of the bug is updated by testers or developers according to the phase of the tracking.

As a twist for this chapter, first, we will be sharing the diagram, then will give the explanation for the lovely folks who need detailed explanation.

1-) Birth

When the testers log the bug report to the defect tracking tool, that bug’s status is “new/open” by default. After the bug is in the system, the tester may have several options to assign to bug to:

- Developers: If the developer responsible for the faulted module is known and QA members and the development members are working closely, testers can directly assign the bugs to the developers.

- Leads: In some instances, lead or senior testers are expected to vet (approve) the bugs written before assigning them to the developers. Or, in another case, leads can have a wider knowledge of the development team, so they can find the related developer.

- Quality Analyst: Usually, testers have the role of a quality analyst role as well, but when a project is huge, there may be a different role on the client side to decide if the bugs should be fixed or not by doing a cost/impact analysis.

2-) Life

Once the bug is assigned to a developer, they start working on the bug to find out the reason for the defect and try to fix it.

The bug does not die as soon as it is fixed. We need to make sure that it is really dead and cannot give any harm. To make sure, the fixed(?) bug is assigned back to the testers and the status is changed to “retest” to see if the defect still occurs.

If the bug is not fixed, it is assigned back to the developers, and this back-and-forth process goes on till it is fully fixed. Similarly, if a fixed bug resurrects from death as a zombie reoccurs, its status is set to be “reopened” (or just back to “open”) and is again immediately assigned to the developers.

Sometimes, defects are not as simple as we would expect, and might take very specific conditions to reproduce, or the time of occurrence of them can be rare. In this case, if the developers cannot reproduce a certain bug after trying for some time, they change the status to “CNR (Cannot Reproduce)” and assign the testers to bang their heads to the wall and update the reproduction steps.

The last circumstance that a bug is still kept alive is when the decision is to hunt down the bug in later releases. It is common to see a lot of defects in a release, but they will have various severity and priorities, so if the developers are drowned with fixing the high-priority bugs and cannot meet the deadline if they attempt to fix all the bugs, the low-priority bugs are postponed being fixed in the later releases. In this case, the bug’s status is set to “deferred”.

3-) Death

And nooow, our favorite. Smashing the bugs!

When the team decides that there is no need to work on a bug anymore, the bug dies. What do we do after that? Delete the bug, right? WRONG! Remember we’ve discussed that one of the reasons we write defect reports is to use them as a future reference.

So, instead of deleting, we keep the bug and set its status to “closed”. Of course, fixing the bug isn’t always the case and there might be several other reasons to close the bug. The laziness of the developers is not included in these reasons.

- The fault is not accepted to be a bug. When the testing team misinterprets a requirement or confuses a feature to be a defect, the assignee developer or lead can close the bug with a comment explaining the reason for rejecting the bug.

- It is indeed a bug but decided not to be fixed. Okay, every bug can be fixed but sometimes to fix the defect, other parts of the application may have to be given up. For example, if there is a minor readability issue that requires the whole design to be changed to fix, that bug will likely be decided as “KS (known-shippable)” and “will not be fixed”.

- The bug is a fully qualified defect and should be fixed, yet it can still be closed. This last situation is when a bug is “duplicated” of another bug. This may seem a bit strange, but in larger projects, there are hundreds of defects reported every release and if multiple teams are working on similar modules, it might be inevitable that a tired tester will overlook the already written bug report (even if he searches in the defect database) and raise the same bug.

When the developers are assigned to the same bug, instead of having a rage attack, they would simply close the bug with the comment linking to the already-written report.

We have covered a lot of things overall. A brief history of bugs, what actually is a bug, some types, and reasons to see them, the purpose of writing defect reports, and the lifecycle of a bug.

The time has come to learn about the bug reports in detail. Next chapter, we will be mastering the craftsmanship of bug writing. It will be a long, but also an equally fun tutorial. Funky promise!